The Frankenstein Machine That Can't Breathe Life

Let's be honest—when you hear "reverse-engineered EUV tool," it sounds like something straight out of a cyberpunk novel. A desperate nation, cut off from critical technology, piecing together the most advanced chipmaking equipment in existence from whatever parts they can scavenge or replicate. It's the ultimate tech heist story. But here in 2025, the reality is far less glamorous. China's so-called "Frankenstein" EUV lithography tool—the one that was supposed to break through Western sanctions—hasn't produced a single working chip. Not one.

I've been following semiconductor manufacturing for over a decade, and I've seen plenty of ambitious projects. But this one? It's different. The community discussions reveal genuine confusion mixed with skepticism. People keep asking: "How hard can it really be?" or "They've had years and billions—what's the holdup?" The answers aren't simple, but they're fascinating. And they reveal why building cutting-edge chipmaking tools might be the hardest engineering challenge humanity has ever attempted.

What Exactly Is This "Frankenstein" Tool?

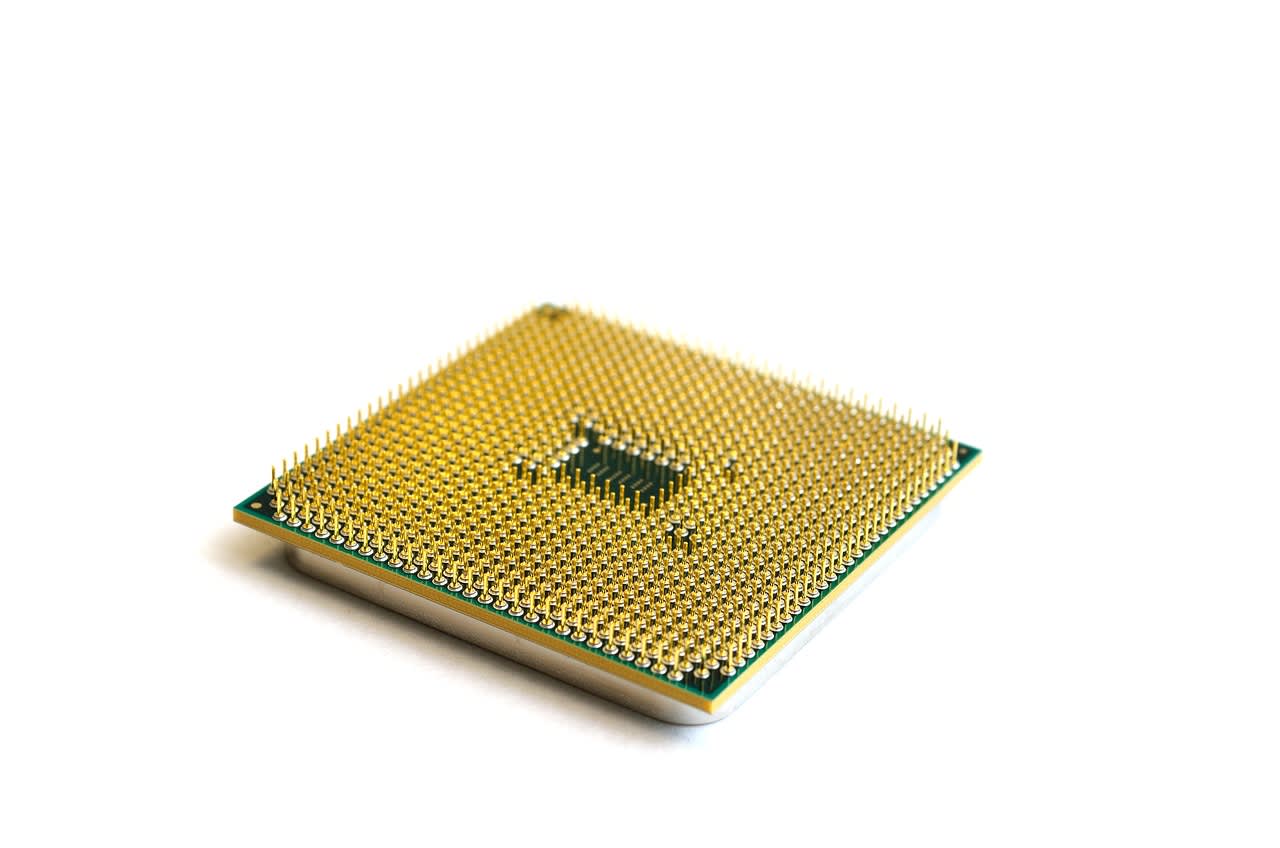

First, some context. EUV stands for Extreme Ultraviolet lithography. It's the technology that lets us print circuits smaller than 10 nanometers—the kind of precision needed for modern processors in everything from smartphones to AI servers. ASML, a Dutch company, is the only manufacturer of working EUV systems in the world. Their machines cost around $150 million each, contain over 100,000 components, and require supply chains spanning dozens of countries.

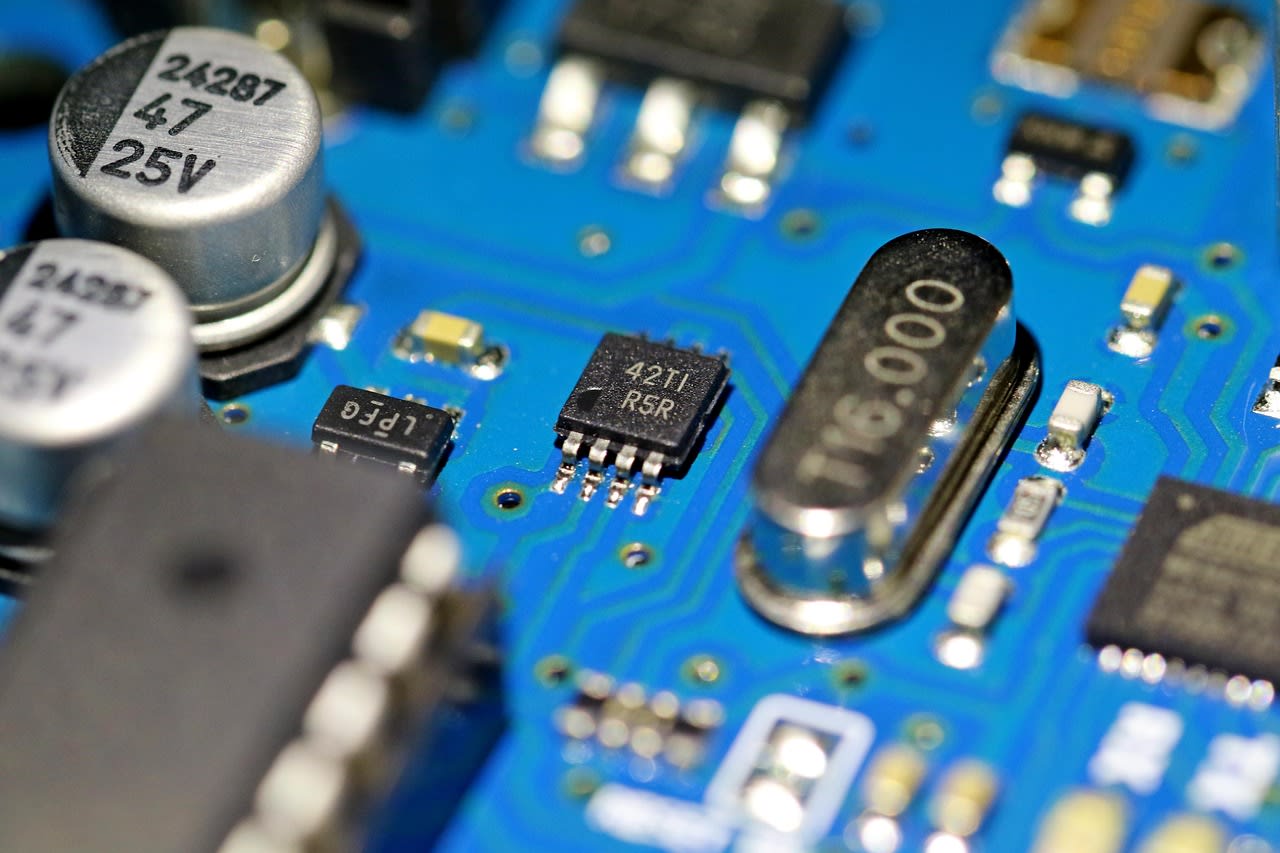

China's version, according to reports and community analysis, is what insiders call a "Frankenstein" system. It's not a clean-sheet design. Instead, researchers and engineers have reportedly been trying to reverse-engineer ASML's technology while incorporating components from various sources—some domestic, some possibly obtained through less-than-official channels. The term "Frankenstein" comes from the community itself, capturing the patchwork nature of the effort: different parts stitched together, hoping they'll work as a coherent whole.

But here's the thing most people miss: EUV isn't just one machine. It's an ecosystem. The light source alone—a system that generates 13.5nm wavelength light by vaporizing tin droplets with a high-power laser—is arguably the most complex part. Then there's the optics, the vacuum system, the precision stages, the metrology tools... each subsystem is a masterpiece of engineering. Trying to reverse-engineer this isn't like copying a smartphone design. It's more like trying to recreate the Space Shuttle by examining photographs.

The Supply Chain Problem Nobody Talks About

Here's where the community discussions get really interesting. Many commenters focus on the obvious technical hurdles: the precision optics, the complex light source. But what they often underestimate is the supply chain nightmare. ASML doesn't build everything in-house. Their EUV systems contain critical components from Germany (Zeiss for optics), the United States (Cymer for light sources, now owned by ASML), Japan, and other specialized suppliers.

China's sanctions-busting experiment faces what I call the "specialized component trap." Even if you can theoretically design something, manufacturing it requires tools, materials, and expertise that might themselves be restricted. For example, those ultra-precise mirrors in an EUV system? They're not just polished glass. They're multilayer mirrors with alternating layers of molybdenum and silicon, each layer just a few atoms thick. The manufacturing precision required is staggering—surface irregularities measured in picometers (that's trillionths of a meter).

And it's not just about making one component. You need to make thousands of them with consistent quality. You need the metrology tools to measure that quality. You need the cleanroom facilities that are a thousand times cleaner than a hospital operating room. You need the vibration isolation systems that can keep everything stable despite earthquakes, trucks passing by, or even people walking nearby. Each of these requires its own specialized supply chain.

Why "Good Enough" Isn't Good Enough

This is where I see the biggest misunderstanding in community discussions. People ask: "Why can't they just make a simpler version?" or "Can't they settle for less advanced chips?" The problem is that EUV doesn't have a "simple" version. It's an all-or-nothing technology.

Think about it this way: if you're 90% accurate with a hammer, you'll still drive most nails successfully. If you're 90% accurate with brain surgery, your patient dies. EUV lithography is closer to brain surgery. The tolerances are so tight that "almost right" equals "completely useless." A mirror that's 99.9% perfect might sound impressive, but for EUV, that 0.1% imperfection scatters enough light to ruin the entire exposure.

From what I've gathered from industry insiders, this is likely why China's Frankenstein tool hasn't produced chips. It might assemble, it might power on, it might even generate some EUV light. But getting all systems working in harmony with the required precision? That's where the real challenge lies. It's not about having a tool that "mostly works." It's about having a tool that works perfectly, consistently, for thousands of hours without failure.

The Software and Integration Nightmare

Here's something most people don't consider: the software. An EUV tool isn't just hardware. It's millions of lines of code controlling everything from the laser timing to the stage movement to the thermal management. This software has been developed over decades, refined through thousands of hours of real-world operation.

Reverse-engineering hardware is hard enough. Reverse-engineering complex control software? That's a different level of difficulty. You're not just looking at what the machine does—you're trying to understand why it does it that way. What edge cases does the software handle? What error conditions does it anticipate? How does it compensate for wear and tear over time?

And then there's integration. Let's say you somehow obtain or replicate individual components. Getting them to work together is another monumental task. The community discussions often mention this—the difference between having parts and having a system. One commenter put it perfectly: "It's like having the world's best orchestra musicians but no conductor. You might get individual beautiful notes, but you won't get a symphony."

The Human Factor: Where Do You Find EUV Experts?

This might be the most overlooked aspect. Building and operating EUV tools requires specialized knowledge that doesn't exist in textbooks. It's tribal knowledge—the kind of expertise that comes from decades of hands-on experience. ASML has been developing this technology since the 1990s. Their engineers have seen every possible failure mode, every weird edge case, every "that shouldn't happen" scenario.

China can certainly hire talented engineers. They can send people to study physics and optics. But there's no substitute for the institutional knowledge accumulated over generations of development. How do you train someone to diagnose a problem that only occurs once every million exposures? How do you teach the intuition that comes from having tweaked every parameter in every possible combination?

Some community members have pointed out that China has managed to make progress in other complex technologies. And that's true—their space program, for instance, is impressive. But there's a key difference: space technology, while complex, often has more tolerance for imperfection. If a satellite component is slightly out of spec, you might lose some capability, but the mission can continue. With EUV, slight imperfections mean zero chips produced.

What Does This Mean for the Global Chip Industry?

So where does this leave us in 2025? Based on the available information and community analysis, China's Frankenstein EUV tool appears to be what one commenter called "a very expensive science experiment." It might yield valuable research insights. It might help train a new generation of engineers. But as a practical chipmaking tool? It seems years away from being operational, if it ever gets there at all.

This has significant implications. First, it suggests that current sanctions are effective at delaying China's advancement in cutting-edge chipmaking. Second, it highlights just how difficult it is to replicate complex technological ecosystems. Third, it might push China to focus on alternative approaches—like advanced packaging of less sophisticated chips, or entirely different computing architectures that don't require EUV.

For the rest of the world, it's a reminder of the fragility of our technological foundations. We depend on a handful of companies in a handful of countries for the tools that build everything digital. That concentration of expertise is both a strength and a vulnerability.

The Road Ahead: Alternatives and Workarounds

If you're following this story, you're probably wondering: what happens next? Based on what I've seen in both industry reports and community speculation, China has several paths forward, none of them easy.

One approach is to continue the reverse-engineering effort but with more realistic expectations. Instead of trying to match ASML's latest systems, aim for an earlier-generation capability. Even 7nm or 10nm chips without EUV would be an achievement, though it would require different approaches like multi-patterning with existing DUV (Deep Ultraviolet) tools.

Another path is innovation around the edges. Some community members have suggested focusing on areas where China already has strengths, like chip design or packaging technology. Advanced packaging—stacking and connecting chips in clever ways—can sometimes compensate for less advanced individual chips. It's not a perfect solution, but it might provide practical benefits while the EUV challenge continues.

There's also the possibility of international collaboration with countries not participating in sanctions. This is tricky given the current geopolitical climate, but technology has a way of finding paths around barriers. Whether through legitimate partnerships or less official channels, knowledge and components might gradually flow.

Common Misconceptions About EUV Development

Let's clear up some confusion I've seen repeatedly in discussions:

"Money solves everything." Not with EUV. ASML has spent over $8 billion and 20 years developing their EUV technology. China could match that investment and still fail because some problems aren't about money—they're about time, accumulated knowledge, and ecosystem development.

"They just need one working machine to copy." This assumes perfect reverse engineering is possible. But even with a complete machine to examine, understanding why it works the way it does is incredibly difficult. And manufacturing the components requires capabilities that might not exist domestically.

"Other countries will help them." Maybe, but at significant risk. The U.S. and its allies have shown they're willing to impose secondary sanctions on companies that help China circumvent restrictions. The economic calculus has changed.

"It's just optics and lasers—how hard can it be?" This is like saying "Space travel is just rockets—how hard can it be?" The individual components might be understandable, but their integration at the required precision creates emergent complexity that's orders of magnitude greater.

The Bottom Line: Patience and Realism

Here's my take after analyzing all available information: China's EUV efforts are real, they're serious, and they're well-funded. But they're facing challenges that go far beyond what most observers appreciate. The Frankenstein tool—if it exists as described—is likely a research platform, not a production tool. It might eventually contribute to a domestic EUV capability, but that's probably a decade away at minimum.

What does this mean for you? If you're in the tech industry, it suggests that the current semiconductor landscape will remain relatively stable in the near term. If you're a policymaker, it shows that targeted technology restrictions can be effective, though they might also spur long-term competition. And if you're just someone fascinated by technology, it's a reminder of just how amazing our current chipmaking capabilities really are—and how difficult they are to replicate.

The story of China's Frankenstein EUV tool isn't over. It will continue to evolve, with breakthroughs and setbacks. But for now, in 2025, the machine remains silent, a testament to the incredible complexity of the technology that powers our digital world. And perhaps that's the most important lesson: some technological achievements represent such concentrated expertise that they can't be easily copied, no matter how much will or money you throw at them.