Imagine you're flying a single-engine plane at 8,000 feet. Suddenly, you can't see. Maybe it's a medical emergency, or perhaps smoke has filled the cockpit. For decades, this scenario often had one grim outcome. But in 2025, that's changing. A piece of technology, discussed fervently in pilot forums and tech circles, is shifting the paradigm: Garmin's Emergency Autoland system. This isn't just your grandfather's wing-leveler. This is an autopilot that can, from cruise altitude, find a suitable airport, configure the aircraft, communicate with air traffic control, navigate traffic, and execute a full-stop landing—all without a single human touch on the controls. The recent discussion on the topic revealed a fascinating mix of awe, skepticism, and deep technical curiosity. Pilots aren't just asking if it works; they're debating how it works, when it should be used, and what it means for their role in the cockpit. Let's unpack this technology, address the community's burning questions head-on, and look at what autonomous landings really mean for general aviation.

From Sci-Fi to Runway: The Genesis of Garmin's Autoland

To understand why this is such a big deal, you need a bit of context. Autoland systems have existed for years in commercial airliners—think Airbus and Boeing jets. But those systems require Instrument Landing Systems (ILS) at the airport, which are expensive, ground-based radio transmitters that give the aircraft ultra-precise guidance. They also typically require a multi-million dollar aircraft with triple-redundant systems. General aviation? That's a different world. We're talking about Cessnas, Pipers, and Cirruses flown by private pilots, often into smaller airports that might not even have a control tower, let alone an ILS.

Garmin's breakthrough, integrated into their G3000 and newer avionics suites, uses a different approach. It relies primarily on GPS and its own database of thousands of airports. When activated, the system doesn't look for an ILS signal. Instead, it scans its database for the nearest suitable runway based on length, orientation, and weather conditions. It then flies a GPS-based approach. This is a monumental shift. It brings a level of safety redundancy to small planes that was previously unthinkable. The original discussion posters rightly pointed out this democratization of safety tech. It's no longer just for the majors.

Breaking Down the Magic: What Actually Happens When You Hit the Button?

So, what's the step-by-step? Based on technical documents and pilot reports, here's the sequence. First, activation is intentional—usually a guarded button or a sequence on the touchscreen. This isn't something that engages by accident. Once activated, the system takes over completely. It announces "AUTOLAND ACTIVATED" and begins a multi-phase process.

Phase one is diversion. Using its onboard databases (which need to be current—a key point pilots raised), it identifies an airport. It's not just picking the closest dot on the map. It evaluates runway length, crosswinds, and even NOTAMs (Notices to Airmen) about closed runways. Phase two is communication. This is where it gets really clever. Using Garmin's AutoCOM function, the system can synthesize a human-like voice to broadcast mayday calls on the emergency frequency (121.5 MHz) and contact the nearest air traffic control facility. It declares the emergency, states its intentions, and even acknowledges instructions. Several commenters were both amazed and slightly unnerved by this feature, questioning how ATC would react to a "robot" voice.

Phase three is the approach and landing. The autopilot flies a precise pattern, configuring flaps and landing gear at the correct points, managing speed, and flaring the aircraft for touchdown. It then applies brakes and brings the aircraft to a stop on the runway. The entire process is designed to be hands-off from start to finish.

The Pilot's Lounge Debate: Trust, Skill, and the "Black Box" Problem

The online discussion revealed a core tension in the aviation community. On one side, you have pilots who see this as the ultimate guardian angel. "It's a get-out-of-jail-free card for catastrophic events," one user noted. For solo pilots, especially those flying over remote areas or at night, it provides a psychological safety net that's genuinely new.

On the other side, you find concerns about skill degradation and over-reliance. A common thread in the comments was the fear of a pilot using it in a situation where they could have handled it themselves, potentially eroding their own proficiency. There's also the "black box" issue. Several technically-minded posters wondered about failure modes. What if the database is outdated and it picks a closed runway? What if it misinterprets a NOTAM? The system is certified to rigorous standards (it's not some beta software), but pilots are trained to trust, but verify. With Autoland, the "verify" part is largely taken out of their hands during the emergency sequence.

And then there's the philosophical question: Is the pilot still the pilot-in-command if the machine is making all the decisions? Legally, yes, but it creates a novel dynamic that the regulations are still catching up to.

Not Just for Emergencies: The Practical Training and Usage Scenarios

While marketed for emergencies, the discussion hinted at other uses. Some pilots speculated about its role in training. Imagine a student pilot practicing emergencies with an instructor. The instructor could simulate incapacitation, activate Autoland, and the student could observe the entire procedure as a perfect demonstration. It becomes the ultimate teaching aid.

There's also the potential for assistance in non-catastrophic but high-workload situations. Think about a pilot encountering sudden severe weather or complex system failures. While the system is designed for total pilot incapacity, having it as an option could allow a stressed but conscious pilot to manage other critical tasks (like troubleshooting a fire or communicating with ATC in detail) while the airplane handles the flying. This isn't the intended use, but it's a scenario several commenters pondered.

For owners considering the system, it's a significant investment, often tied to a full Garmin glass cockpit upgrade. It's not a standalone box you bolt on. You're looking at a major avionics overhaul. For a new aircraft like a Cirrus or a high-end Cessna, it's increasingly becoming an available option. For older planes, the cost of retrofitting might be prohibitive, which leads to a valid concern about a safety divide between the haves and have-nots in aviation.

The Regulatory Hurdle: How the FAA Approved a Robot Pilot

One of the most insightful parts of the source discussion focused on certification. How did this get past the FAA? The key is in the system's limitations and design philosophy. It's not an autonomous flying system for everyday use. It's a single-function emergency system. Its activation is a deliberate, last-resort action. The FAA certified it under strict conditions, likely as a supplemental system rather than a primary flight control.

Furthermore, it's built on top of Garmin's existing, already-certified autopilot and flight control systems. The new magic is in the software logic—the decision-making for airport selection, communication, and sequencing. This software underwent what's likely thousands of hours of simulation and real-world testing. A commenter with apparent industry knowledge pointed out that the certification likely involved proving the system's reliability was orders of magnitude higher than the probability of the dual emergency it's designed for (pilot incapacity and a need to land immediately).

The system also has built-in inhibitions. It won't attempt a landing in hurricane-force winds or on a runway that's clearly too short. If conditions deteriorate below its minimums during the approach, it will execute a missed approach and try another airport. This layered logic helped satisfy regulators that it wouldn't make a bad situation worse.

A Look Under the Hood: The Tech That Makes It Possible

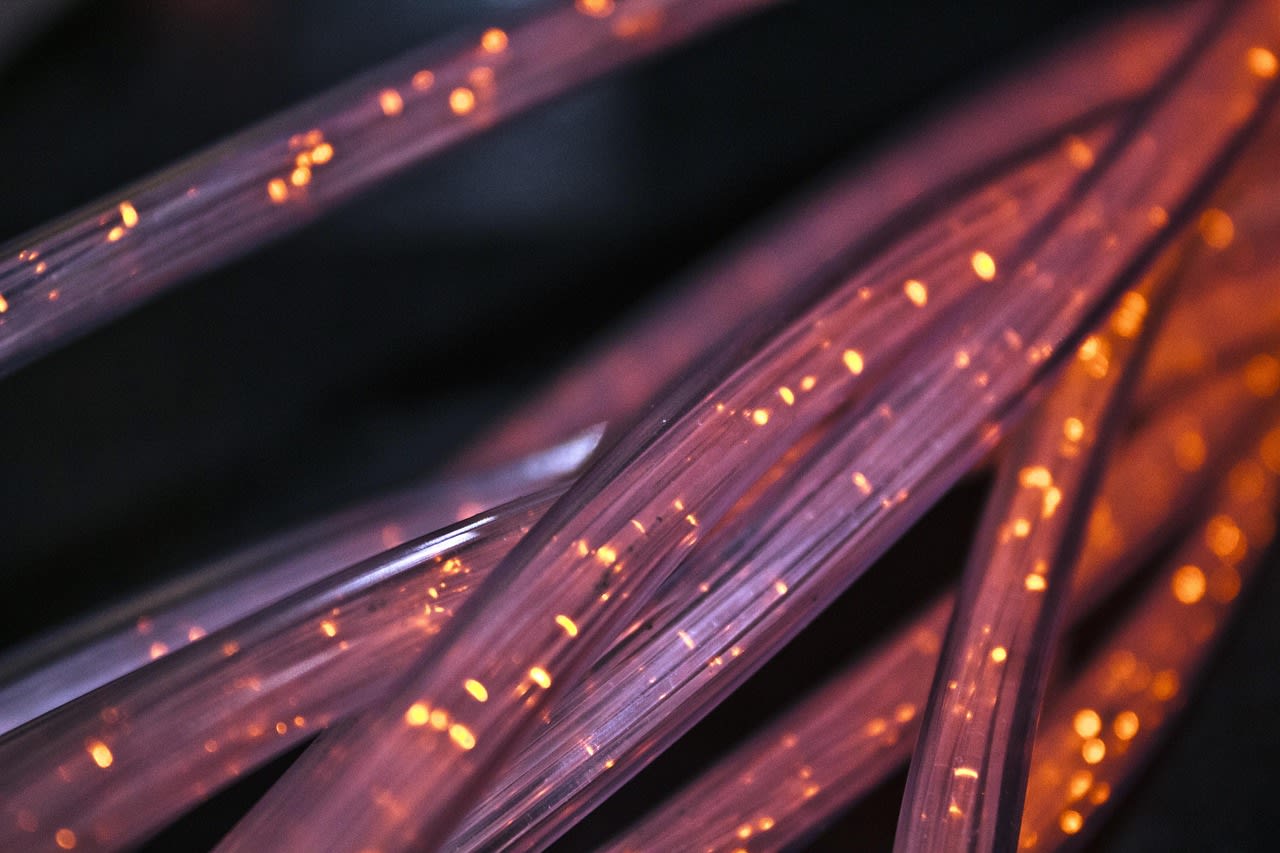

Let's geek out on the components, because the engineers in the thread were doing just that. At its heart, the system is a fusion of several mature technologies:

- Triple-Redundant Computers: The Garmin G3000 suite uses multiple independent flight management computers that cross-check each other. If one disagrees, it's voted out.

- WAAS GPS: This isn't your phone's GPS. Wide Area Augmentation System GPS provides the extreme precision (down to about 3 feet vertically) needed for an approach without ground guidance.

- Detailed Global Databases: This is the secret sauce. The system has access to constantly updated databases of airports, runways, terrain, and obstacles. Keeping these databases current via subscription is critical, a point many pilots emphasized.

- Digital Autopilot Servos: These are the muscles that move the flight controls. They're powerful, precise, and designed to overcome control forces to fly the programmed path.

- Voice Synthesis & Radio Management: The AutoCOM technology handles the external communication, a feature that sparked as much discussion as the landing itself.

It's the integration of these systems under one unified software command that creates the autonomous capability. It's less about inventing new hardware and more about writing incredibly robust, fault-tolerant software to orchestrate the existing hardware in a completely new way.

What Pilots and Owners Need to Know Before Relying On It

If you're a pilot or aircraft owner looking at this tech, here's the practical advice distilled from the community's wisdom. First, it's not a substitute for proficiency. You must maintain your flying skills. This is a system of last resort, not a convenience feature. Second, database management is non-negotiable. An outdated database could direct the plane to a runway that's now obstructed or closed. Treat these updates with the same seriousness as checking your fuel.

Third, understand its limitations. It works within a defined envelope of weather and aircraft conditions. It may not handle a massive, unexpected wind shear on short final as well as a seasoned human pilot might. Fourth, brief it. If you have passengers, consider briefly explaining what the big red guarded button is for (without causing alarm). If you fly with other pilots, discuss it.

Finally, test it in a simulator. Garmin offers training software and device trainers. Use them. See the prompts, hear the voices, and follow the sequence in a risk-free environment. Knowing what to expect reduces panic and confusion in a real event. As one experienced pilot in the thread put it, "You don't want the first time you hear the autoland activation voice to be when you're actually having a heart attack."

Addressing the Big Questions and Concerns Head-On

The discussion was full of specific, sometimes anxious, questions. Let's tackle a few directly.

Q: What if there's other traffic in the pattern?

A: The system uses traffic awareness (via ADS-B In) and will announce its intentions. It's up to other pilots and ATC to clear the path. It assumes a priority emergency status. This is a valid concern and highlights that the airspace system still requires human coordination.

Q: Can it land at any airport, even a grass strip?

A: No. It's programmed for paved, public-use runways of sufficient length that are in its database. It won't pick a private grass strip.

Q: What stops someone from maliciously activating it?

A: The activation is guarded or requires a specific software menu sequence. It's not easy to do by accident or in a struggle.

Q: Is this the first step toward pilotless air taxis?

A: In a way, yes. It's a massive proof-of-concept for fully automated flight in the national airspace. The tech developed here directly informs the eVTOL and autonomous cargo drone projects. But for manned general aviation, the pilot remains firmly in command—until they literally can't be.

The Road Ahead: Where Does Autonomous Flight Go From Here?

Garmin's Autoland isn't the end of the story; it's a bold beginning. The conversation among pilots shows both excitement and healthy caution. The next steps are predictable: refinement. We'll see systems that can handle more complex weather, perhaps even selecting an off-airport landing site in truly desperate situations. The communication function will become more sophisticated, allowing for two-way dialogue with ATC.

Cost will also come down. As with all avionics, what's a $100,000 option today may become a $20,000 option in a decade, making it accessible for more aircraft. The regulatory framework will evolve too, potentially creating new ratings or endorsements for pilots who operate with these systems.

But the core lesson from the 2025 discussion is this: technology is offering a new answer to aviation's oldest and most feared question: "What if I can't fly the plane?" The answer is no longer just hope and luck. It's a series of precise electronic decisions, made at lightning speed, with the sole purpose of saving lives. Whether you view it as a miraculous guardian or a disquieting shift in control, one thing is undeniable—it changes the game. And for a pilot facing an unimaginable crisis, that change might just be everything.